Montserrat is a small island in the West Indies. It is approximately 39.5 square miles with about 5,000 inhabitants in 2013.

The country is currently in the midst of redevelopment after Hurricane Hugo destroyed much of the island’s infrastructure in 1989, and then its active ash volcano ravaged the southern region with pyroclastic flows between 1995-1997.

These natural disasters have largely resulted in emigration to the United Kingdom and North America, and the island continues to rebuild today. Read more about Montserrat’s history and culture.

Montserrat’s nickname is the “Emerald Isle of the Caribbean,” not only because of its lush green landscape, but also because the island has a distinctive historical connection to Ireland.

Montserrat was settled in the early seventeenth century by Irish Catholics seeking refuge from religious persecution in Ireland and other British colonies such as neighboring island St. Kitts as well as Virginia. By the late seventeenth century, British and Anglo-Irish plantation owners in Montserrat had developed a slave economy and African slaves planned their first large-scale uprising there for March 17th, 1768. As the story goes, the slaves knew that Anglo-Irish masters would be celebrating St. Patrick’s Day and otherwise distracted with drink and dance. The rebellion failed when someone revealed the plan, but Montserratians today commemorate St. Patrick’s Day as the first attempted slave insurrection on the island. It was a major step in the movement towards emancipation, which was finally achieved in 1834 (see Howard A. Fergus, 1975).

Traces of Irishness in Montserrat still exist today in the form of place names such as St. Patrick’s, Kinsale, and Carr’s Bay. Family surnames such as Sweeney, Allen, and Murphy are prevalent among this largely West African-descended population, who adopted the names of their Irish masters upon emancipation and/or are the descendants of mixed racial relations.

From this history arises the cultural myth of the biracial or “black Irish” people of Montserrat, who are said to have lighter skin than the rest of the island’s population. Some say that they speak a creole English with words borrowed from Irish Gaelic and pronounced with traces of an Irish brogue (see Eddie Donoghue, 1995). Watch this short documentary from Ireland’s TG4 TV station in 1976 about the “Black Irish of Montserrat“:

However, the use of this “Black Irish” terminology has been the subject of much debate among scholars concerned with Montserrat’s history, and many argue that a significant Irish influence on Montserratian language and dialect is doubtful (see J.C. Wells, 1980).

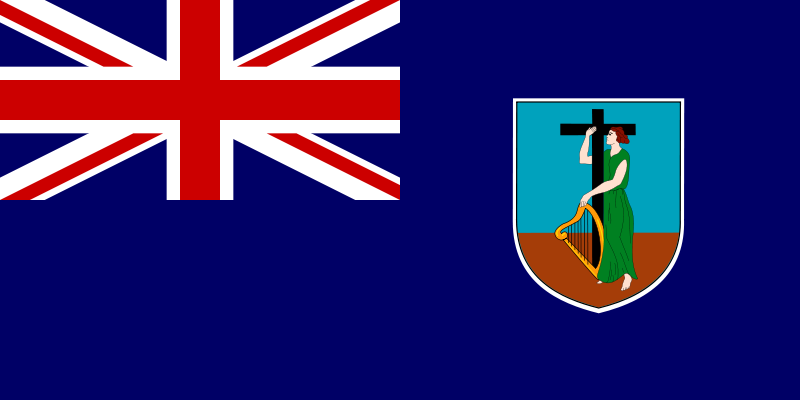

Nevertheless, Montserratians today frequently make use of Irish symbols such as the shamrock and Irish harp on national emblems such as their flag and passport stamp (see Howard A. Fergus 1981). “Erin” also holds a black cross along with the Irish harp on the national flag, indicating Montserrat’s Irish and African histories.

In Montserrat, “Irishness” is frequently encountered: Irish harps are stamped in passports, and during St. Patrick’s Week, shamrocks are displayed in store windows and Irish flags hang in pubs. In Ireland and the US, these symbols signify Irish pride, but in Montserrat they inspire freedom across national, racial, and ethnic boundaries.

“Emerald Splendour” at Montserrat’s annual Christmastime Festival in 2013

During Montserrat’s annual St. Patrick’s Week Festival, these symbols become animated through dance, music, and costuming. The local masquerade dance apparently features elements of Irish polka steps and West African dance postures, and their colorful costumes represent freedom from oppression.

See the masquerade dance in this video (starting at 2:00):

The festival runs simultaneously with an annual African Music Festival (launched in 2013) during a week that celebrates the island’s unique “triangle” of Montserratian, Irish, and African heritage. As Premier Reuben Meade explains:

“Over the years, we have celebrated St. Patrick’s as an Irish festival, but not the same way as they celebrate it in Ireland. We are celebrating a fight for freedom. We always saw the Montserrat-Irish connection. This year, what we have done is to close that triangle. So you have Montserrat, Ireland, and Africa…. And so we must not see ourselves as Irish or Africans or Caribbeans–we must see ourselves as people of the world, irrespective of our culture, and we will come together….” (personal correspondence, March 17, 2013)

Sources:

Donoghue, Eddie. “The Black Irish of the Caribbean.” The St. Croix Avis, Friday, May 12 1995.

———. “Montserrat Masquerade: Cultural Preservation in the Modern World.” 2001.

Fergus, Howard A. History of Alliouagana: A Short History of Montserrat. Plymouth, Montserrat: H. A. Fergus, 1975.

———. “Montserrat ‘Colony of Ireland’: The Myth and the Reality.” Studies 70, no. 280 (1981): 325-40.

———. Montserrat, Emerald Isle of the Caribbean. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1983.

———. Montserrat: History of a Caribbean Colony. London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1994.

———. Montserrat in the Twentieth Century: Trials and Triumphs. Montserrat: UWI School of Continuing Studies, 2001.

Messenger, John C. “African Retentions in Montserrat.” African Arts 6, no. 4 (1973): 54-57, 95-96.

———. “The Influence of the Irish in Montserrat.” Caribbean Quarterly 13, no. 2 (1967): 3-26.

———. “Montserrat: The Most Distinctively Irish Settlement in the New World.” Ethnicity 2 (1975): 281-303.

———. “St. Patrick’s Day in ‘the Other Emerald Isle’.” Éire-Ireland 29, no. 1 (1994): 12-23.

Wells, J. C. “The Brogue That Isn’t.” Journal of International Phonetic Association 10 (1980): 74–79.

Contact for more sources.